At RavenSong, our approach to harvesting is grounded in returning to the land, unlearning colonial ways of knowing and being, and actively reconnecting with the ocean, forests, and all that sustains us. It is through these relationships with plants, waters, stories, and ceremony that we root our work. We hope that this moment of reading invites the reader and greater community into a deeper understanding of an Indigenous woman's lived experience—one of remembering, reclaiming, and reweaving her way back to land, culture, and collective community care. This is not just a personal journey, but part of a larger movement of healing, resurgence, and responsibility to future generations

Harvest like your ancestors, with intention.

This isn’t just a saying, it’s a worldview. It’s a way of moving through the world with humility, awareness, and purpose. For me, intention means recognizing that every action on the land is a dialogue with the spirit of place and the people who came before. It’s knowing that harvesting medicine is not simply about taking it’s about relationship, respect, and reciprocity. I was raised within this understanding, shaped by the stories, songs, and land-based teachings of the Wet’suwet’en Nation. As a member of the Laksilyu Clan, I carry the teachings of our Chiefs Dinï’ze Kloum Khun (Alphonse Gagnon) and Dinï’ze Smogelgem (Warner Naziel), of Laksamshu (Fireweed and Owl) Clan and the protocols that have grounded our people for generations. These teachings aren’t abstract—they were lived and embodied by my auntie, Elder Mary Mabel Joseph, Timberwolf, a Matriarch of the Gidimt’en Clan, fluent speaker, and tireless cultural educator. Through cultural camps and ceremonies, she showed us that harvesting was never just about gathering plants, making ndn ice cream or listening to our creation stories—it was about showing up in a good way, doing the dishes and doing something because it's right and not because someone is watching.

To harvest with intention is to know where you stand, to consider the wellbeing of the ecosystem, the community, and the generations to come. It means asking: Is this plant thriving? Am I giving back more than I take? Do I know the story of this place? Am I prepared to offer something in return—whether it’s tobacco, a song, or simply care? In a time when disconnection from land and culture is so common, intention becomes a radical act. It calls us back to ceremony. It calls us to listen more than we speak. To remember that harvesting like leadership, like storytelling isn’t about ownership. It’s about stewardship. My grandmother, Emma Derrick, raised me as her daughter. She made sure I went to every cultural camp—even when I resisted. Out of all my siblings, I was the one she chose to push the hardest. I understand now: she saw the seeds that needed to be nurtured. The future that needed preparing.

Consider Whose Land You Are On

Before you pick a single leaf or dig a root, pause. Whose traditional territory are you in? What stories belong to that land? What protocols and relationships exist that you might not see? Growing up, Auntie Mabel, Timberwolf taught us to know our own lands, to recognize the gifts and responsibilities that come with being Wet’suwet’en. She was born under a tree by a lake in her father’s territory, delivered by her mother’s hands, and raised in the language and strength of her people. Her life and teachings are reminders that land is not just resource: it is relative.

Give Back to the Land

Offerings are part of relationship. When harvesting, bring tobacco, sage, or seed-infused water. Leave something with intention and gratitude. Give your energy back in ways that help the ecosystem remove invasive species, volunteer for local restoration efforts, and speak up for Indigenous land protection.

Harvest What is Abundant and Thriving

Before taking a plant, ask yourself: Is this thriving? Is it being over-harvested? Can I harvest in a way that allows this patch to regenerate? Let the plant speak. Watch the signs. Learn its season. Be gentle. Avoid digging out the heart of a medicine patch. Let it breathe and continue. These aren’t just environmental practices: they are acts of cultural survival. Timberwolf, who tanned hides and made moccasins, who carried the language of our people through decades of erasure, also taught that strength comes from restraint. To harvest ethically is to live in a good way.

Walk Lightly, With Joy

Harvesting is not only about discipline: it is also about joy. Be playful. Bring your children. Sing. Laugh. Let it be ceremony. Use baskets or bags made from natural fibers. Avoid plastic. Pack out what you bring in. Let your footprint be light. Experience JOMO: the joy of missing out on stimulating events and rather choose the intention of being quiet, quieting the mind and head to the sea and land. The moments of walking through the forest barefoot, laying tobacco at the base of Devil’s Club, teaching little ones the names of plants in their own language: these are the memories that shape identity and stewardship.

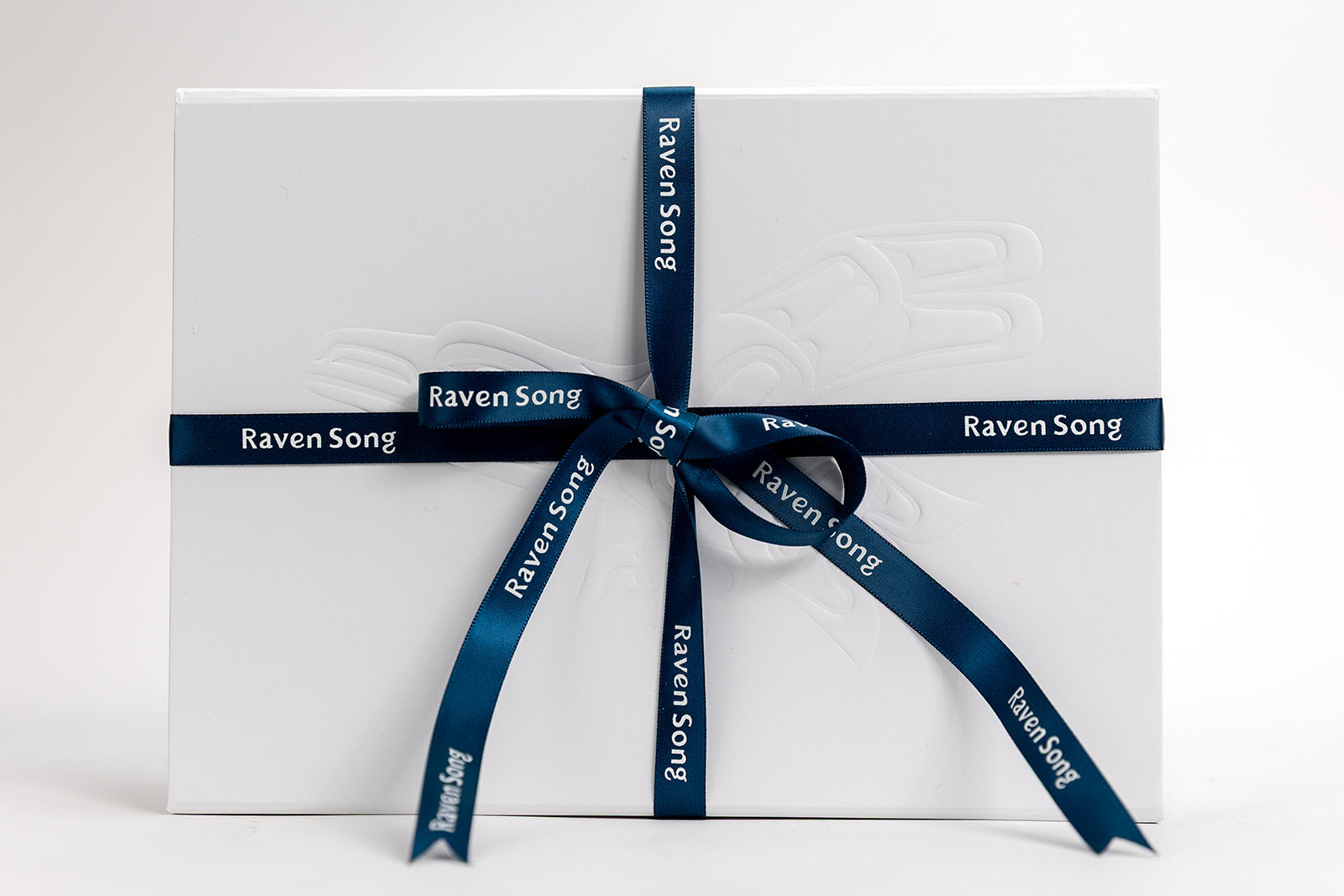

At RavenSong, each bar of soap is made with plants that were honored, not exploited. This is our way of living ceremony. As you move through forests, beaches, travelling to territories that you are a guest and visiting, carry this with you:

🌀 Harvest with care

🌀 Respect the original stewards of the land

🌀 Leave offerings

🌀 Give back more than you take

🌀 Teach the next generation

🌀 Be a good ancestor

Save & Share. Tag us with your harvesting stories. Let’s return together to sea, land, story, and self.

#RavensongRituals #StorytellingisCeremony #PlantMedicine

---

Read this reflection by RavenSong owner, Alissa Assu and it's inspiration behind the "From Grief to Disconnection: Walking Gently with the Plants Again" story to share with each of you.

As a youth, I was shaped by the stories, songs, and land-based teachings of the Wet’suwet’en Nation. I was raised by my grandmother, Emma Derrick, Skokumahlyte who took me in as her daughter and, as a single mother, raised a total of five children. I come from the Laksilyu Clan and carry the teachings of our Chiefs Dinï’ze Kloum Khun (Alphonse Gagnon) and Dinï’ze Smogelgem (Warner Naziel), of Laksamshu (Fireweed and Owl) Clan. My early connection to harvesting, plants, and ceremony was rooted in cultural camps led by my Auntie, Elder Mary Mabel Joseph, Timberwolf: a Matriarch of the Gidimt’en Clan, fluent language speaker, and knowledge keeper who has spent decades ensuring the survival of our cultural practices. Out of all my siblings, I was the one she pushed the hardest. At the time, I didn’t always understand why. But now I see clearly Emma though she herself was never taught how to give or receive love in the ways we often expect. What she did have was determination, cultural knowledge, and a deep sense of responsibility to raise us within our Wet’suwet’en ways.

Much of my early resistance came from the weight of what I witnessed as a child. My grandmother brought me to feast halls not only for clan business, but for funeral feasts and payback feasts. By the time I was still very young, I had already attended more ceremonies rooted in grief, loss, and responsibility than in joy and celebration. These early experiences shaped me deeply. They taught me how central ceremony is in our culture—that governance, justice, and mourning are all carried through community gatherings. But they also left me with unprocessed sorrow, held in a child’s body with no outlet for understanding or healing. This heaviness was compounded by the racism I experienced in daily life both overt and systemic. The marginalization, the way our culture was treated as lesser, the silence around our history—it was all part of a colonial system that taught me, subconsciously, to turn away from my own roots as a form of protection. To survive, I distanced myself from culture, language, and even the land.

It wasn’t until I attended Langara College that I began to truly understand the depth of our shared history. For the first time, I was formally introduced to the truths about residential schools, the Sixties Scoop, and the legal structures that devalued our identities. I learned that we live in a country where, to this day, if a white woman marries a Native man, she gains Indian status—but if an Indigenous woman married out, she and her children would lose theirs. These revelations cracked something open in me. I was angry. Grieving. Overwhelmed. I began learning and unlearning colonial ways of being rebuilding a relationship with myself and my culture on my own terms.

This journey didn’t end in the classroom. Every job I’ve ever held from frontline service work in community to roles within government—has added another layer to my understanding. I saw how policy fails to reflect the realities of our people. I witnessed how systems replicate trauma when they are disconnected from land, language, and kinship. And I carried the weight of these truths with me.

But in that weight was also a calling: to return.

To return to the land that holds my ancestors.

To return to the sea that sustained our nations long before colonization.

To return to the teachings I once resisted not out of rejection, but out of pain.

And so I’ve made my way back reading, learning and harvesting plants with intention. Grounding my business in ceremony and building foundations what that means alongside my own healing journey and in relation to my community. To find joy in the same places that once felt heavy. Land and sea are not only part of my healing with self but also being kinder to myself. Now as an adult with more understanding more education, more emotional capacity I can hold the complexity of that experience. I’ve come to know the history of my family, of the Joseph and Derrick lineages, and how our stories are interwoven with resistance, survival, and strength. Now, every time I step into the forest or along the shores of the Salish sea, I can begin to feel moments of reconnection. I remember the laughter around the fire, the stories that made us proud, the hands of Elders showing us how to harvest with care. Recalling the happier memories of moose hanging in our backyard shed. I now feel the possibility of celebration again but now with my two children and parter Cody Assu.